Leopardus jacobita, the mythical Andean Cat is one of the 38(?) species of the world’s wild cats; it is one of the most threatened in the American continent and is considered by many experts as one of the most difficult to spot in the wild. Its environment is increasingly being fragmented and disturbed, that’s why it has been regarded as an Endangered species by the International Union for the Conservation of Nature (IUCN).

On the other hand, the Pampas Cat (Leopardus colocolo) is a highly versatile feline and widely distributed throughout South America. A recent publication regards each one of its numerous races a valid species taxon. Hence, Leopardus garleppi stands out as a new species for Chile’s mammalian fauna.

The following are field notes of a recent expedition to Chile's High Andes, which we hope will be useful to cat enthusiasts and researchers.

In late 2019, our organization Far South Expeditions, carried out a new recce trip in search of Andean Cat (Leopardus jacobita), one of the world’s most threatened and unknown felines, concentrating our efforts on the Lauca River area and Las Vicuñas Nature Reserve (Arica and Parinacota Region, Chile). We carried out our expedition to the Chilean Altiplano between December 17-22, 2019.

The Andean Cat ranges in Chile along the Andes Mountains, from its northern end to the central area of the country, with recent records for the Andes above Santiago. Its range also includes the high Andean plateau of adjacent countries (i.e. Peru, Bolivia and Argentina), ranging from 3,000 to above 5,000 m.a.s.l. (9,800 – 16,400 ft.a.s.l.).

Its distributional range is very ample but its population density is extremely low, making it an extremely rare and scarce cat species. In addition, the high altitude environment where it lives is very arid and harsh, having very extreme temperatures, conditions that make its search even more difficult. As a comparison, the Andean Cat is 90% less frequent than the sympatric Puna Pampas Cat (Leopardus garleppi), which has a somewhat similar highland distribution.

In mid-December 2019, we arrived to Lauca area, a truly imposing habitat. The Chilean altiplano is a vast territory with endless horizons.

December 17

The sky was totally clear and the sun was really scorching; we knew that the mornings would be often like this, so we decided to take advantage of it by surveying the habitat and its main topographic features. The puna, due to its altitude and extreme climate, imposes many physical challenges. Our search area was located above 4,000 meters (+13,000 feet), in an extraordinary volcanic setting, many peaks rise above 6,000 meters above sea level (+19,000 ft.a.s.l).

Right after our arrival to the area, we were busy retrieving the camera traps that we had already placed on site a couple of months earlier, last October. Those were situated along a prominent creek. The first camera was situated on a plain, although it did not have any photos; apparently the settings were wrong, that was really unfortunate as it was a very good place, where there were numerous tracks of wild cats, including Puma. The second and third cameras, were places at the entrance of a very narrow gorge, rising through a secondary ravine; each one documented part of the total scene. On these two cameras we got 24 cat photos, in sequences of three photos each; the camera traps recorded foxes, viscachas, other rodents and some birds also.

After a very productive day in the field, we arrived to our lodging, a high-Andean farm house with its typical architecture; built in adobe, very simple and comfortable and with a good space to organize ourselves. Its cleanliness was extremely valued, especially when traveling with lots of gear to these arid and dusty locations.

At night we were busy checking the retrieved photos of the camera traps, trying to identify which species of cats were captured and if there was a relationship between them.

We found out four sequences from the same cat species, identified as Puna Pampas Cat (Leopardus garleppi), in addition to a sequence of Andean Cat (Leopardus jacobita); for the latter sequence, we couldn’t make a straightforward ID at the very beginning.

| Fecha | Hora | No. de Fotos | Dirección | Id. Cámara |

| 14-10-19 | 23:46 | 3 | Norte | #2 |

| 03-11-19 (*) | 02:44 | 3 | Norte | #2 |

| 09-11-19 | 05:10 | 6 | Sur | #1 |

| 09-11-19 | 05:22 | 3 | Sur | #2 |

| 30-11-19 | 22:44 | 6 | Sur | #1 |

| 30-11-19 | 23:00 | 3 | Sur | #2 |

| 08-12-19 | 18:28 | 3 | Norte | #1 |

Table 1. Camera trap photo sequences

December 18th

We woke up very excited, with the rewarding results from the previous day and we dedicated ourselves to prospect the plateau before dawn. The magnitude of the task is indeed overwhelming, as we aim to check each sector, paying attention to the slightest movement, and also to the alert calls from Andean Geese, Andean Lapwings and Crested Ducks. We also observed the behavior of many viscachas, which jumped from rock to rock, going up the steep scree slopes.

We found scat and tracks of cats and foxes too, along the gorges; those were found up and down, indicating that we had found a corridor. We also identified footprints on the margins of a valley and inside dry riverbeds, caused by floods during the rainy season. All these signs helped us to have a more thorough idea of how these cats move around their territories. We went through different environments, trying to characterize them. On dense tola scrub (Baccharis) sites, we found many tracks, with erratic patterns, indicating perhaps pauses and permanence; in more open situations, such as Coiron bunch-grass (Festuca and Stippa) steppe habitat, we didn’t find any traces.

During the afternoon we were relocating the camera traps, this time on a higher location of the same ravine where we obtained the previous photo sequences. This sector was chosen considering the large number of footprints. It was the rise of a steep canyon, almost at its highest point, with a very narrow pass.

December 19th

We headed towards Salar de Surire, an important and vast flat salt basin, located in the heart of the homonymous Natural Monument; this place is a true magnet for wildlife, attracting herds of Vicuñas (Vicugna vicugna), flocks of Puna Rhea (Rhea pennata), family groups of Puna Tinamou (Tinamotis pentlandii), abundant viscachas and their young, plus a large assemblage of birds, including Aplomado Falcon, Gray-bellied Shrike-Tyrant, White-fronted Ground-Tyrant and the three species of highland flamingos (Andean, Puna, and Chilean Flamingo).

We spent the whole day exploring the great salt flat but unfortunately did not see the cat, despite the large number of tracks. Late in the afternoon, the weather changed drastically; the sky was covered with menacing dark clouds and a sudden lightning storm announced a torrential rain coming from Bolivia. We had to go down from the summit where we were, to avoid potential lighting strikes!; threating thunder less than three seconds away, indicated an obvious risk, as we were walking with monopods and camera gear. We left them on the ground and we waited for the threatening clouds to recede a little bit. We decided to go back and return to our lodging; in the middle of the road section, torrential rains blocked the view, making almost impossible to advance due to the poor quality of the dirt road; we wondered where the Andean Cat would find refuge in these conditions.

December 20th

The intense cold of the night froze the wetlands, locally known as bofedales. From very early, on we observed how the frost slightly was disappearing; we were already watching at this early hour, there is always the chance that a cat could approach to hunt the abundant birdlife, especially Puna Tinamou. At dawn, bird species such as several Ground-tyrants and Cinclodes, Andean Lapwings, Puna Snipe, ducks and Andean Geese gather around the wetlands to feed. We patiently walk through small streams and rocks. It was very rewarding even to find petrified tracks, probably from Pleistocene fauna; many of these tracks have similarities to modern camelids and others belonged to larger mammals.

Right after sunset we made a final site inspection, this time by car and using the support of flashlights; we illuminated the road sides in search of any mammal movement. After a few hours … success! About 60 meters away, a small mammal showed up, its eyes gave it away, although quickly disappeared through the scrub vegetation and we could not even identify it. Sure was a small cat. Tomorrow we will check the area again so we left a waypoint on our GPS.

December 21st

Before dawn, we were already at the same location of our previous sighting; we used our flashlights again, thoroughly illuminating the dense scrubland. Apparently, cats like to walk among them at night. Alas, we didn’t find him or her again. We decided to climb a hill nearby, trying to detect any movement while the the sun was getting higher; noisy tinamous were advancing from the scrub to the open plains, along with flocks of Andean Goose. We saw pretty much everything, but not the cat we spotted the night before; apparently it was just passing lonely individual.

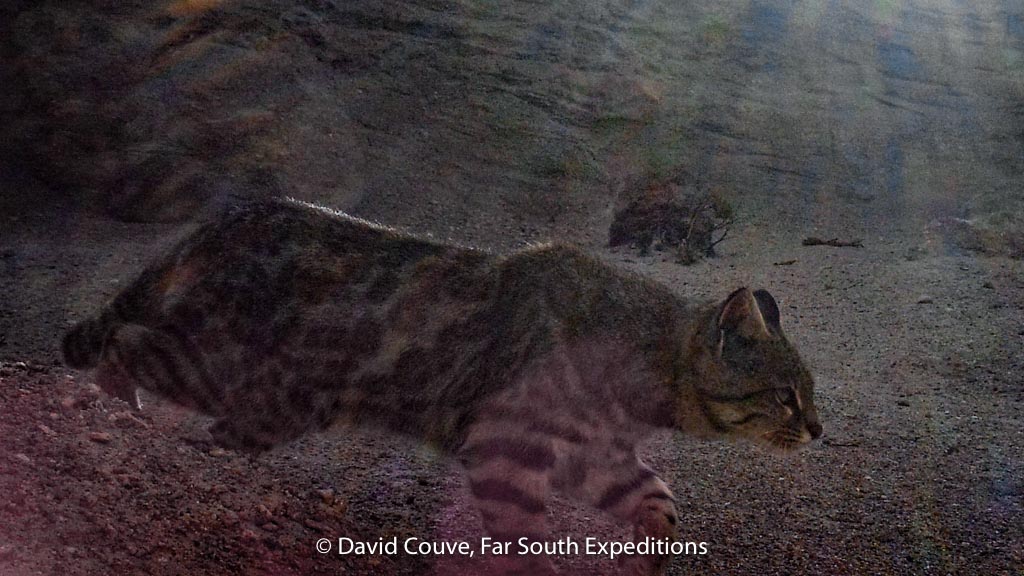

At noon we decided to get some rest in a rocky area and had our picnic, always very alert, observing the small dry riverbeds and between the scrub. Success again! We were checking a ravine flanked by dense bushes; a well-camouflaged cat, was lying and resting on that place. For such instances you must be prepared and Enrique had his camera ready and took a few photos. The cat quickly left the place before the others in our party could do the same. Most likely, such elusive behavior responds to feel threatened, as cats are still highly persecuted in the area. For a good reason! How many times have we seen stuffed cats heads and skins in the small Andean villages!

Still, the brief scene stayed in my head, although it wasn’t Andean Cat. The cat we observed and documented had a dense gray fur, large yellow eyes, a pink rinary nose, and two black lines across its cheeks. What we concluded was that we watched a gray morph of Puna Pampas Cat (Leopardus garleppi). Some authors have recently suggested a rearrangement of this species complex, assessing each race/subspecies with a valid species status. Our cat had a gray tail and black stripes; from the head to the back it had a black longitudinal line; on its legs, black rings that faded towards the body. It was mere 10 seconds, but was totally worthwhile the whole morning of searching and even much more, this was just getting more and interesting.

During the afternoon we continue checking the fairly open terrain with binoculars in hand. Most of the time it is about checking the sites in search of any movement or sign; you just need to have a great deal of patience and determination and wait for nature to do its thing. We took advantage of the opportunity of being in such interesting habitat, by observing and documenting lizards, spiders, mice, groups of vicuñas grazing, nesting Mountain Caracaras and even a Puna Hawk, watching us from the highest part of the cliffs.

We decided to return to the original ravine, where we previously had success with our camera traps. Before reaching the top of the canyon, we discovered a new cat. This time along a faded trail; it turned his back to us and a gave us a very brief opportunity to photograph it.

It was a long way off though, but we were able to see its gray coat and brown spots. The photos will reveal its true identity. Then he/she got into the ravine and disappeared again; we think it went down, and it was impossible to find it again. We spent a few more hours checking the area and decided we must give it its space. We went back to dinner to get some rest; the next day we have planned the long journey back to Arica, but first we need take advantage of the last morning in Lauca area.

December 22th

At the end of our 5-day expedition, we went through the last valley suggested by a local farmer. We advanced along the trail, which was on the edge of the upper part of the canyon, looking at the great valley that was hidden behind. We got a stunning view illuminated by the morning sun, revealing a valley with all the conditions to be the perfect habitat for Andean Cat.

It was beautiful to say goodbye to my first expedition in search of the cats of the Chilean puna, knowing that I should return the following year and thoroughly explore this new valley, full of possibilities.

Summary

We have recorded during the months of October, November and December 2019:

• Three camera trap photo sequences of the Puna Pampas Cat, Leopardus garleppi.

• One camera trap photo sequence of Andean Cat, Leopardus jacobita.

• One sighting at night, without photographs of an undetermined cat.

• A photographic record of Puna Pampas Cat, Leopardus garleppi. A rather particular individual, with gray fur and without the typical spots on its flanks.

• A photographic record of Andean Cat, Leopardus jacobita.

(1) (1) If you were interested in this article, we recommend the excellent report of the expedition by Jon Hall, Phil Telfer y Enrique Couve en 2018. Read more.

(2) The cover photo of Gato Andino, which illustrates this article, was obtained by guide Roberto Donoso during one of our expeditions to the Salar de Surire in 2008.

References:

3 Comments

Leave your reply.