Exploring the desolation, in search of one of the least known birds of Chile and Patagonia. An expedition literally to the "ends of the earth" aiming to generate new information about a "ghost bird". A good British friend and a best field ornithologist, Mark Beaman wrote some time ago: "A true bird of mystery: wanted by so many, seen by so few."

Fuegian Snipe Expedition to the Wollaston Archipelago, Chile

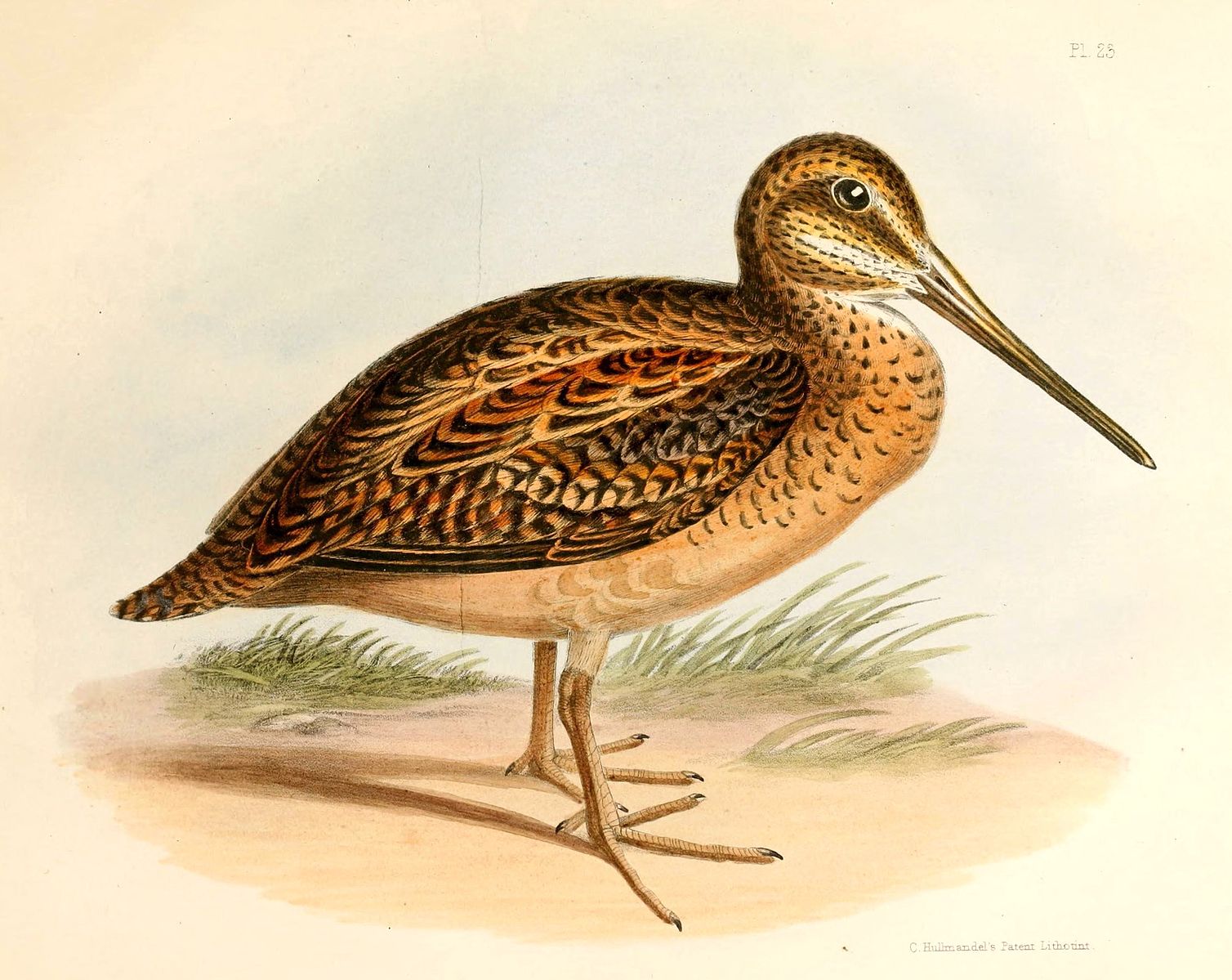

This bird of mystery came to light when originally described in 1845 by George R. Gray, based on a specimen collected on Hermite Island, Wollaston Archipelago, in the southern tip of Chile, during the expedition commanded by James Clark Ross aboard the legendary ships HMS Erebus and HMS Terror. Since its discovery about 175 years ago, the Fuegian Snipe (Gallinago stricklandii) is still remains as one of the great ornithological mysteries in the Neotropics. Most aspects of its natural history are totally unknown to us.

A handful of references, perhaps no more than 20-30 records and personal communications, seem to indicate that the most exposed archipelagos to the extreme weather of the Southern Ocean (Pacific and South Atlantic), in the area between the Magellan Straits and the Cape Horn in Chile, in addition to Staten Island, a remote and seldom visited possession of Argentina, is the desolate home of this stocky built snipe. fuegian snipe expedition

The talented and young naturalist Percy Reynolds visited the Wollaston Islands in 1932 and vividly described the vocalizations and drumming flight of this Gallinago, as well as provided the first remarks about its breeding behaviour. Reading his field notes and impressions about a cold and windy summer night in that archipelago, turned out to be a captivating and irresistible invitation to follow his footsteps, many decades later.

A couple of years ago, Claudio F. Vidal, Mark Beaman, Alejandro Kusch and myself decided to carry out an expedition dedicated to the study of the Fuegian Snipe. At that time we chose the remote Noir Island as our destination, but hurricane-force winds and heavy swell prevented us from even reaching the island; the trip was not safe in those conditions and we decided to abort the mission when we were barely five nautical miles from that desired island.

January 2020 presented itself as an excellent and new opportunity to carry out a new expedition and the Wollaston Archipelago, better known for the southernmost of its islands – Hornos (or Horn) and its famous Cape, was selected as a new chance to find our nemesis bird.

The expedition began from Punta Arenas with a fairly short one-hour flight over the Darwin Mountain Range, the last stronghold of the Patagonian Andes, at these latitudes. Puerto Williams, the southernmost city in Chile and the world, is located on the southern shores of the Beagle Channel. A beautiful setting of pebble beaches, subantarctic beech forests and tantalizing unexplored peaks were the prelude to our epic ornithological expedition. Upon arrival, we set off on a walk up to Cerro La Bandera (The Flag Hill) which produced great views of White-bellied Seedsnipe, one of the most difficult birds of Tierra del Fuego. In addition we saw a few White-throated Caracaras, together with the abundant Yellow-bridled Finch and Ochre-naped Ground-Tyrant were part of a very productive start of the field records.

The next morning we boarded the 56-ft yacht Chonos, an acquaintance of many past adventures which gave us full access to this myriad of islands at the end of the world. Navigation through the scenic and narrow Murray Pass was fast and efficient; its sheltered waters are home to an array of waterfowl including Flightless Steamer-Duck, Kelp Goose, Ashy-headed Goose and Crested Duck. The numerous islets and harbored surprises such as the rare Snowy Sheathbill, of which we saw three individuals. A relatively easy day and almost perfect weather. We anchored that first night in the quiet of the protected Bertrand Island. fuegian snipe expedition

We weighed anchor at dawn and our destination ahead, the dreamed Wollaston Islands. The possibilities are numerous, many islands to explore and a very limited time. Will we be able to find our elusive Fuegian Snipe? Our concern is reasonable as one must to consider the treacherous weather which could cancel our expedition at any time. Our initial anxieties dissipate quickly as we sailed the waters of the vast Nassau Bay, with many pelagic seabirds to study including Black-browed Albatross, Southern Giant Petrel, White-chinned Petrel and Sooty Shearwater. Numerous Magellanic Diving-Petrels and Fuegian Storm-Petrels kept us busy and entertained, trying to photograph them. Southern Fur Seal along pods of Peale’s Dolphin and Chilean Dolphin were the marine mammals of the day. Paso Bravo, located between Freycinet and Wollaston Islands, provided us a magnificent spectacle when we observed a fast-swimming flock of around 100+ Rockhopper Penguins. Caleta Martial, on Herschel Island, becomes our first landing at 1445 in the afternoon on January 6. What a beautiful and promising island! Named after the 18th-century German-British astronomer William Herschel, this island is vast and desolate. Hills of about 200 meters high, extensive Sphagnum peat bogs and stunted forests of Antarctic beech, is all there is. We explored from the beaches of the cove to the peaks of the highest hills; three, four and five hours of restless search, and nothing! However, we found numerous marks and signs indicating the snipe presence. The feast of birds this afternoon walk did not include Fuegian Snipe, but we found many others such as the Striated Caracara, Plumbeous Rail, Patagonian Sierra-Finch, Thorn-tailed Rayadito and Magellanic Tapaculo. Second night, safely anchored and surely we will dream of elusive snipes. fuegian snipe expedition

January 7th. It’s my birthday, and the weather is still mild but will not last for very long. This is our window of opportunity and according to the forecast it will hold only for last for two to three days at most. We opted for the safest option. We will head south straight to Hornos Island and focus our search on that remote island, the one that has produced the most records in recent years. Two hours of sailing on a channel with abundant shoals and dramatic islets, the sunrise turns out to be glorious! Our arrival at Hornos Island is very early because there are many tourist boats visiting during the summer months and we prefer to anticipate and have the place for ourselves. At 8am, a familiar silhouette turns out to be our first encounter with this elusive bird. A vast peat bog of Sphagnum moss, covered with reeds (Marsippospermum grandiflorum) and prostrate cushion-like bushes (Bolax gummifera) turns out to be the preferred habitat of Fuegian Snipe. The place is flooded with dozens of small ponds and flanked by a tangled stunted forest of Antarctic beech (Nothofagus antarctica), known to botanists as krummholz. The environment is constantly battered by an inclement oceanic climate, very rainy and extremely windy. It seems to us that this exposure to the ocean favors the presence of the snipe.

Our first individuals turn out to be a couple (male and female) together with a tiny, colorful and down-covered chick, of roughly one week old. The image is touching and exciting for any bird enthusiast. A slight and bouncing movement, back and forth especially of the rear part of body is the characteristic way they move and seem the chick mimic this form of displacement from an early age. The birds were quite silent, as they didn’t emit any audible vocalizations during the period that we observe them. This pair of snipes seems to make a regular use of the space, remaining active throughout the day although at intervals; every 20 or so minutes they moved and look for food; after that they rested and doze, and moved again. They remained virtually motionless and very well camouflaged, for long periods of time, and when they felt detected, they remained static, being extremely difficult to spot. While foraging, they actively probe the mossy and muddy terrain with their long, thick and blunt-tipped bill; they also probe into peat and cushion-like Bolax bushes. They left evident marks in the form of numerous holes in the vegetation in addition to the characteristic feces. We did observe how they show a preference for nematode worms, although the food supply may also be supplemented by spiders and ground-dwelling insects. Something of great interest is that all the observed and photographed birds had visible ticks lodged in the eye area, something that certainly deserves to be studied and see if this parasite is specific to the snipe. This pair from Isla Hornos was joined by another specimen observed in a distant swamp. An exceptional day, where our success was not in the highest part of the hills, but rather in the gently sloping bogs at no more than 250m high, a short distance away from the coast. We anchored at Caleta Leon, on Hornos Island.

January 8 – The barometer dropped and announced a front approaching from the south, although the weather is still quite nice and calm. Cape Doze, on Wollaston Island is our base for today, although we quickly realized that despite of some snipe signs, we will not be lucky to find more specimens. We must continue moving, and our best option seems to be to sail west and focus our last search on Hermite Island, the very place where the first explorers collected the type specimen of the species. Southe American Sea Lions and Peale’s Dolphins are our company across that stretch of sea, in addition to exceptional sightings of an Orca pod! The island is huge and with a difficult topography; there are no many good anchoring coves in the selected search area, although we did take the risk. The hostile climate is announced with gusts of wind and this will limit our time spent on the island. There are two more specimens that we managed to see, this time somewhat darker than those observed at Hornos Island. A walk through the headland has revealed its presence in advance, given the large number of feces and marks on the vegetation. The Striated Caracara and the Chilean Skua nest on this island and we wonder if these will have a significant effect as predators of Fuegian Snipe and its chicks. Another question along the way, but we believe that it may be of importance. fuegian snipe expedition

January 9 – Bad weather pushed us to seek shelter at Bayly Island, at the famous Romanche anchorage. Hurricane force winds of 20 to 30 knots prevent us from exploring the most promising points of the archipelago, but we are more than satisfied with having observed five adults plus that chick, both on Isla Hornos and Isla Hermite. It is more than obvious that the population density of this species is very low, in a potentially suitable and at the same time vast territory.

January 10 – Cabo Doze was chosen as our shelter for the penultimate day of search, this time facing very adverse weather conditions, with a lot of wind, rain and cold. The climate has its reputation well earned in these latitudes. White-chinned Petrels and Sooty Shearwaters are a constant company as we cross the Franklin Channel with rough seas, in addition to flocks of Magellanic and Rockhopper penguins. We surveyed the Ottaries Isles and there are carcasses of dead birds and mammals everywhere. It is obvious that there is illegal hunting on this islet and the most probable thing is that fishermen still use the local fauna as food and bait for their crab traps. Flightless Steamer Ducks to Sea Lions, the shoreline is littered with half-decomposed skeletons and carcasses. There are no traces of Fuegian Snipe in this place, although the birdlife is varied but very wary to human presence. We observed several songbirds such as Magellanic Tapaculo, Thorn-tailed Rayadito, Austral Thrush, Rufous-collared Sparrow, Dark-faced Ground-Tyrant and larger birds such as Chimango Caracara, Striated Caracara and Chilean Skua, also nesting here, in close contact with Magellanic Penguins burrows. The South American Snipe is quite common here, as well as White-rumped Sandpiper and even a Chilean Swallow, at the southernmost part of its summer range.

January 11 – Wind gusts of up to 45 knots and a threatening swell are more than enough warnings. We must return to the sheltered waters of the Murray Canal. We crossed Nassau Bay with a stern wind and without major difficulties to arrive at the historic Wulaia Bay, on the west coast of Navarino Island around 3pm. A well-deserved toast among the expedition members gave us the satisfaction of an ambition and task accomplished. The Islote Conejo (Rabbit Isle) is the place of our last anchorage.

The next day heading to Puerto Williams from where we returned to Punta Arenas.

There are many questions, although the data from this first field campaign is promising. We should return later this year if possible, on a new Fuegian snipe expedition and only if the ongoing coronavirus worldwide pandemic allows it.

Resources

Kusch, A. & M. Marin (2010) Distribución de la Becasina Grande Gallinago stricklandii (Gray, 1845) (Scolopacidae), en Chile | Distribution of the Fuegian Snipe Gallinago stricklandii (Gray, 1845) (Scolopacidae), in Chile. Anales Instituto Patagonia (Chile), 2010. 38(1):145-149. link

Leave a Reply

Your email is safe with us.