Black-browed Albatross, Thalassarche melanophris / © Rodrigo Tapia, Far South Exp

Like almost all living creatures, birds need to drink water, but what about seabirds? This is a question not so simple to answer, especially in the case of pelagic seabirds that spend most of their time in offshore waters, and whose only source of water, therefore, is the sea. The problem? Salt water, because of the high concentrations of salts and minerals present in it, is toxic to drink for the vast majority of organisms. So, how do seabirds deal with this physiological problem?

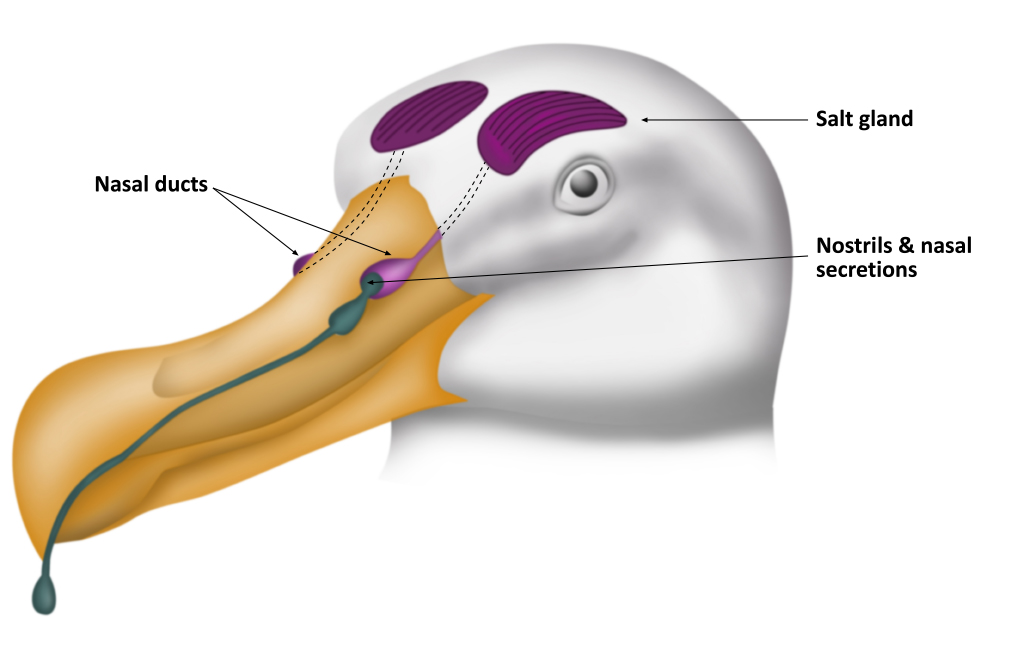

Well, the answer is rather simple but it works in a complex way. Seabirds possess a gland, the Supraorbital or salt gland, sitting on the supraorbital groove in the frontal bone. This salt-excreting gland has been developed by some bird groups along avian evolutive history in order to be able to feed on high mineral content food like fish or algae. Avian kidneys are not efficient enough to get rid of this excess salt in the bloodstream, nor do birds have sweat glands to help along with the process, and so the gland absorbs the excess salts from the blood through the thin walls of the capillary network and collects it so that it is continually dripping along the gland duct and out trough either the nostrils or beak.

Birds like penguins, petrels, albatrosses, gulls, cormorants and marine ducks have developed this gland to be more efficient than a kidney, so the concentrated brine that comes out as the excretion is about five times that of the sea water ingested by the bird in the beginning. Sodium and Chlorine are the main output chemicals, but Potassium, Calcium and Bicarbonate are also eliminated like this.

A seabird with a salt water volume equivalent to 10% of its blood volume, can get rid of 90% of this excess salt in three hours, and the excreted fluid contains roughly a 5% of salts, so this organ accounts for the ability of pelagic seabirds to survive in the middle of the ocean for months and sometimes years without going anywhere near a source of freshwater.

Leave a Reply

Your email is safe with us.